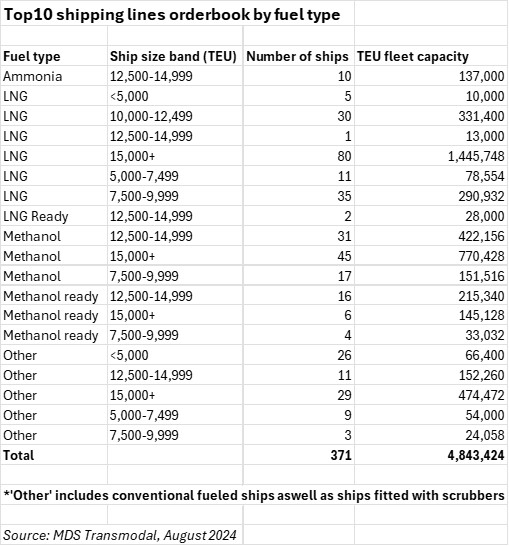

The world’s ten biggest container shipping lines have a total of 371 vessels on order, of which 162, totalling 2.2 million TEUs, are LNG powered, with 80 of these vessels over 15,000 TEUs, representing 1.44 million TEUs.

Ordering of these ships has been labelled as “bizarre” by University College London’s Dr Tristan Smith, who said that carriers appear to be looking at each other and copying ordering errors.

“All they [the container lines] seem to be doing is looking at what each other is ordering and then matching that, in an ever-tightening noose of cognitive dissonance, perhaps because none of them are brave enough to read the IMO’s revised strategy? Or really figure out what it means for rate of change of technology,” claimed Smith, who is also a member of the UMAS maritime consultancy.

Effective regulation on LNG will not come from the EU’s FuelEU regulation for another 10-15 years, which Smith said could “perhaps be one explanation for this bizarre ordering of LNG dual fuel ships”.

He added: “Bizarre because last year the IMO made it clear that it was going to set its mid term measures to deliver 50-60% GHG intensity reduction in 2030 and 90% lower GHG intensity reduction in 2040.”

According to Smith, the IMO regulations, which are expected to be introduced by 2027, are far more stringent than the EU laws and “based on our group’s analysis [UMAS], I can’t see how under realistic biofuel prices, it will be possible to competitively operate a dual-fuel LNG asset into the 2030s.”

The IMO’s revised strategy made it clear that it will set its mid-term measures to deliver a 50-60% GHG intensity reduction in the 2030s and 90% lower GHG intensity reduction in 2040.

Smith suggests: “Maybe they [the carriers] are presuming that the IMO isn’t going to enact the revised strategy in its regulations when it agrees them next year, which seems an odd bet to place given that in 2023 IMO surprised many by adopting more stringency in the revised strategy than they had expected.”

Container shipping’s orderbook up to 2029 deliveries currently stands at 371 ships with a combined capacity of 4,843,424 TEUs.

A Maersk spokesman told Container News the company believes that LNG can decrease GHG emissions by a “modest” 10-15% on a well-to-wake basis, if used with the correct engine technology, but the company concedes: “it is not a solution to the [global warming problem.”

Lookout Maritime CEO, Martin Crawford-Brunt believes that two-stroke engines suffer 0.2% methane slip, compared to 3.1% from four-stroke engines, which he says, “negates the benefits of LNG”.

Current regulations from the EU mean that by pooling just a few lower emission vessels with the rest of the fleet, a company can average out reductions across its fleet, reducing FuelEU regulatory costs.

Faïg Abbasov, Shipping Programme director, Transport & Environment which is a member of Say No To LNG (SNTL), said: “Pooling is not a loophole. It is intended to enable the uptake of zero/near-zero emission vessels as companies renew their fleet as oppose to marginally improving older vessels through biofuel blends. Allowing targets to be achieved on a fleet wide rather than an individual vessel basis allows for ambitious new shipbuilds instead of having to do small retrofits on the whole fleet.”

Another SNTL member, the German environmental group NABU, whose transport policy officer Lukas Leppert argued: “The pooling mechanism won’t lead to more GHGs to be emitted overall as the whole fleet still has to meet its reduction targets. Having single ships be noncompliant will be compensated by the over-compliant ambitious newbuilds.”

Pooling offers significant cost incentives according to Crawford-Brunt, which made Maersk’s decision to order LNG powered ships, an apparent strategic U-turn, “inevitable, because they would not be able to compete against MSC and CMA CGM.”

Mary Ann Evans

Correspondent at Large