It is seven years since the first Triple-E vessel was delivered by Daewoo Shipbuilding. The Maersk McKinney Møller was handed over by the South Korean yard to the Danish carrier in 2013 amongst much fanfare.

One of the, perhaps, unforeseen consequences of the megaship era has been the increase in safety issues that have been realised as more cargo means more misdeclared containers, more equipment that can fail and generally more accidents.

Last year was a big year for vessel fires and cargo losses, but while the ships have been in danger, the same cargo is handled by terminals and in larger quantities, though, of course, for dockers and other staff when a fire breaks out at a terminal the handling of the fire is very different and the workers can move away.

Even so, the results of poorly stacked containers or misdeclared cargo at a terminal can be devastating as seen by the 2015 fire at Tianjin, which caused the deaths of at least 173 people and injuries to hundreds of others.

A rise in the number of ship fires, as a result of intentional misdeclaration of cargo or the improper declaration of what is in the container, allied with a failure for regulatory authorities to keep up with the pace of change. But as the TT Club’s risk management director Peregrine Storrs-Fox pointed out to Container News, “Misdeclared cargo loaded onto a container ship is also misdeclared at the container terminal.”

Storrs-Fox believes that there is a need for a far-reaching programme of education for those that are not logistics experts, but who are a crucial link in the supply chain.

The evolution of container ships has been mirrored by the development of the supply chain; however, the regulatory authorities cannot keep up with the pace of change. And while the shipping industry may be embracing modernity, with digital developments, the majority of shippers are small businesses, who sometimes consolidate their cargoes, even before they reach the ship or terminal.

One such industry, in Indonesia, supplies charcoal for barbecues, with some of this fuel having had an accelerant added for easy lighting. According to Storrs-Fox, these producers are very small businesses, often consolidating cargo through intermediaries before employing a freight forwarder to book the cargo on board a vessel.

These original shippers are unaware of the requirements for labelling, packing and loading containers aboard a vessel. What is necessary is to develop the supply chains in such instances by educating those that use them.

This is where the triple-E’s are critical. Education, evaluation and enforcement are today’s triple-E’s for container cargo transportation. In the terminals and inland transportation there are risks for operators and others without the critical knowledge being imparted to those that load cargo.

Without the education, the evaluation of risk cannot be critically measured and neither the education nor evaluation matter unless regulations are enforced and are enforceable.

Sadly, the Tianjin accident, of the 12 August 2015, remains as a tragic illustration of the consequences of a failure of the triple-E’s that was brought into sharp focus by the failures, which saw a series of explosions resulted in the death of at least 173 people, many of them firefighters.

It is worth looking at the failures at the Tianjin Dongjiang Port Ruihai International Logistics container terminal and warehouse for hazardous materials, if only to remind the industry of what can happen if cargoes are not properly handled.

The warehouse at Tianjin was owned and operated by Ruihai Logistics, and according to local reports a 2014 government document states it is a hazardous chemical storage facility for calcium carbide, sodium nitrate, and potassium nitrate.

Safety regulations that required public buildings and facilities to be at least 1km away were not followed, and local inhabitants were unaware of the danger.

It is reported that the local authorities had acknowledged that Ruihai Logistics were poor record keepers, that there was damage to the office facilities and “major discrepancies” with customs meant that they were unable to identify the substances stored.

State media revealed that Ruihai had only received its authorisation to handle dangerous chemicals less than two months earlier, meaning that it had been operating illegally from October 2014, when its temporary license had expired, to June 2015.

When fire broke out, fire fighters responded but were unaware of the chemical cocktail stored in the warehouse and had used water to douse the flames. Further chemical reactions saw two massive explosions, the second of which was visible from space, with satellites able to pick up the event.

More than 100 of the total death toll were first responders, while some 797 people were badly injured. Moreover, some 304 buildings, 12,428 cars, and 7,533 intermodal containers were damaged. The cost to businesses as a result of the break in the supply chain caused by the explosions was estimated at US$9 billion.

According to Storrs-Fox, the fire fighters would have used a system of boundary cooling, where water is used to reduce the heat without dousing water directly onto the fire. This would have saved many lives. A similar incident in Vancouver was dealt with by fire fighter in such a way leading to better outcomes.

However, the key message is that education, evaluation and above all enforcement were absent from the Tianjin tragedy.

One of the key elements for a terminal fire as pointed out by Sean Dalton, who chairs the cargo committee at the International Union of Marine Insurers and is head of marine at Munich Re in the US, is that while fighting a fire at sea is very challenging for the crew, and there are a lot more resources on shore to deal with any incidents “there are greater aggregations” of potentially dangerous cargoes in a terminal. Effectively that means there is more to burn should an accident occur.

In such situations, it is important to know who is regulating the use of such potentially dangerous cargoes. The International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS Code), which is part of the Safety Of Life At Sea (SOLAS) convention ISPS makes governments, port and vessel operators, and staff responsible for safety and security at ports. And ISPS is enforced by local jurisdictions.

Storrs-Fox says that besides ISPS and a few notable exceptions such as the International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code and Verified Gross Mass (VGM) regulations and the guidance from IMO in MSC.1/Circ.1216 (2007) ‘Recommendations on the Safe Transport of Dangerous Cargoes & related Activities in Port Areas’, essentially ports are regulated locally.

“It is always a delicate discussion at the ship/port interface – practicalities mean that there needs to be an effective hand-off between international and national law, regulation and enforcement,” said Storrs-Fox.

Nevertheless, Richard Brough of the International Cargo Handling Coordination Association (ICHCA) told Container News, “The industry needs to wake up and smell the coffee.” Brough believes that the responsibility must lie with the name on the bill of lading while SOLAS and the IMO set the parameters for regulation Port State Control need to police the industry effectively.

The 2012 MSC Flaminia fire, which, according to a 2018 court ruling, was caused by a runaway chemical reaction within three tanks of divinylbenzene (DVB) – a monomer additive that is used in making plastic resins – and a spark created by the crew’s reasonable firefighting response.

The US District Court for the Southern District of New York Court concluded that the manufacturer of the DVB, Deltech, was aware of the substance’s tendency to self-polymerise and generate large amounts of heat if exposed to temperatures over 29degs centigrade for a prolonged period.

Reports suggest that the DVB cargo was at the New Orleans terminal for 10 days stored in the sun, before being loaded onto the MSC Flaminia. The ruling by the US court was that the freight forwarder, Stolt Tank Containers, and the cargo manufacturer were responsible for the Flaminia accident which killed three crew, it was the first-time shippers and forwarders were held responsible for such an accident according to Dalton.

Stolt said, at the time, that it was “disappointed” with the court’s ruling.

Terminal storage was a causal factor in the accident according to the US court and as such the event could easily have occurred in New Orleans and created another Tianjin type incident in the US.

However, in the Flaminia case, the forwarder was seen to be partly at fault and for some, the non-vessel operators (NVO) can be risky.

Tom Boyd, a spokesman for APM Terminals, North America, Maersk’s terminal operating company, believes that the greatest risk for both vessels and terminals are the consolidated containers, where NVO’s mix cargo into a single container.

“NVO margins are slim and they will mix many cargoes into a container and these can be problematic,” Boyd said.

A freight forwarder responded to APMT’s view, arguing that, “Misdeclaration takes place mainly by shippers in order to save money and not by NVO’s. I don’t believe that any serious NVO will not declare the cargo to the shipping line although it is declared to the NVO by a shipper.”

According to the forwarder the company has received many requests from shippers not to declare IMO cargo, because they try to cut costs. “The same happens, for example when we load marble and they want us to load 30 tonnes of cargo although such a weight is above containers’ specifications.”

Container weight and packing can also be an issue, with Storrs-Fox pointing to the death of a driver and his assistant when their truck, carrying a load of printing paper, overturned in Liverpool. An investigation revealed that the paper had been stowed in the centre of the container and as the truck negotiated the first corner its cargo shifted overturning the truck.

Even so, the TT Club rejected the APMT view on consolidated cargoes, Storrs-Fox believes that “if containers are stopped or held up due to irregularities, communications with the other groupage customers can be complex. For these reasons, I suspect that the management time and reputational risk [for the forwarder] far outweigh any additional profit they might make.”

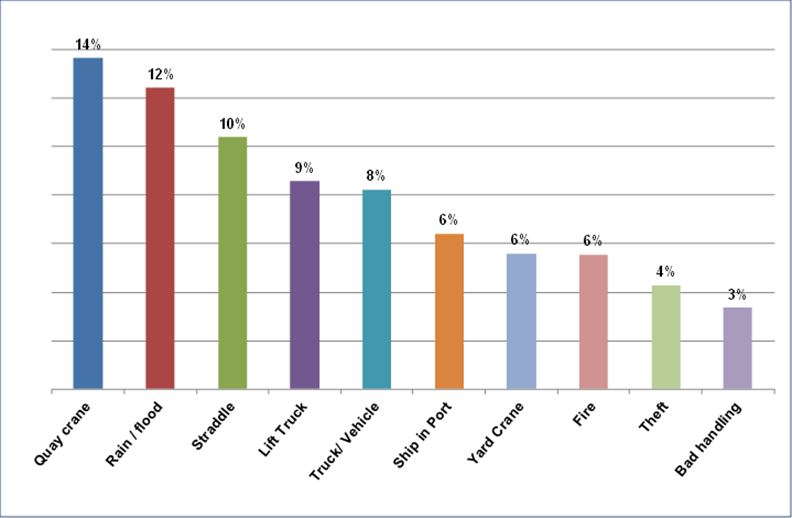

Clearly, fire hazards can result in the massive loss of life and severe injuries to local populations, not to mention the cost to community life and the losses encountered by businesses, these events are some of the most dramatic, but fire, according to cargo insurer TT Club, ranks only eighth in its list of ten highest risks at container terminals.

“Some 44% of the fire cost in container terminals arises amongst lift trucks; these need detection and suppression systems in the engine compartments, as well as assiduous attention to proper maintenance,” said the insurer.

For the TT Club and its cargo integrity collaborators, including the ICHCA and the Port Equipment Manufacturers Association (PEMA), the greatest cause of accidents in terminals are quay cranes, “It has remained for a number of years the single most costly insurance claim, with all-too-frequent incidents involving boom collisions, gantry collisions or stack collisions,” said the group.

In its list of terminal hazards, flooding is the second most prevalent cause of container damage with terminals being low lying, the risk of flooding remains high. The third greatest cause of accidents is straddle carriers.

“Manual straddle collisions and overturns, besides causing damage, usually result in serious bodily injuries. Like most incidents, these are commonly due to human error. While these are top-heavy items, with inevitable blind-spots, there are monitoring technologies available to ensure mechanical performance and also support user behaviour and training,” said the group.

One of the issues that was not mentioned by ICHCA, the TT Club and PEMA in their briefing was the possibilities of reefer container fires which have been a significant problem in the past, and was raised as an issue by Storrs-Fox in his discussions with Container News.

He said that some reefer containers have had “arcing problems” where current jumps between electrodes with a flash, which can result in fire.

One prominent terminal operator, who wished to remain anonymous, told Container News, “We put these DG [dangerous goods] and reefer containers under greater CCTV scrutiny, checking for leakage, smoke etc on a constant basis. We have specially trained emergency response teams who will be the first on the scene if there is any incident.”

This responsible terminal operator has trained staff that will respond to incidents including fires and are trained in how to deal with dangerous and other goods. However, for terminals operated by less diligent owners, the goal of safe shipping becomes more problematic.

According to Dalton, the industry incurred cargo losses of between US$2-3 billion in the Tianjin event and similar losses in super storm Sandy which hit the Port of New York and New Jersey three years earlier. There are possibilities for some scrutiny before containers are allowed on board a ship or into the container yard that will increase safety and cut losses.

Dalton cites a 2019 National Cargo Bureau (NCB) survey that was conducted for the Cargo Incident Notification System (CINS) that looked at 500 import containers of both standard and hazardous goods into the US.

According to the inspection report, 55% failed with one or more deficiencies; 69% of the import containers containing dangerous goods failed; and 38% of containers with dangerous goods exports failed.

Of the import containers with dangerous goods, 44% had problems with the way cargo was secured, 39% had improper placarding and 8% had misdeclared cargo. Of the export containers with dangerous goods, 25% had securing issues, 15% were improperly signed and 5% were misdeclared, though some of these did not present safety issues.

“Prevention is better than a casualty,” according to Dalton, and some of the initiatives by the lines to monitor containers and identify which boxes are suspect and should be investigated are a positive sign that the industry is attempting to address the problems.

The ability for the industry to successfully intercept all misdeclared cargoes amongst the millions of containers shipped each year is simply not possible concedes Dalton, “the sheer size of the business means it is impossible to look at all containers,” he said. Lines will need to use an imperfect system of checking the country of origin, the trade routes and cargo descriptions and tip-offs to try to intercept suspect boxes.

According to Storrs-Fox, the best method to improve safety within the supply chain is to educate those operating within it. By educating all the participants, they will be better able to evaluate the relative risks of the cargo they are packing and transporting. And any improper declarations of cargo should be minimalised. While the intentional criminal misdeclarations must be dealt with by the law and so a workable system of enforcement must also be a priority.

Managing Editor

Nick Savvides